A brand is a word. That’s it. To ask how much a brand is worth is to ask how a word gets its meaning.

The brand of a merchant or salesman used to be a proper noun: his surname. His challenge, if he wanted to keep trading with others, was to keep his “good name,” by performing acts of reputational vigilance known as keeping his “word.”

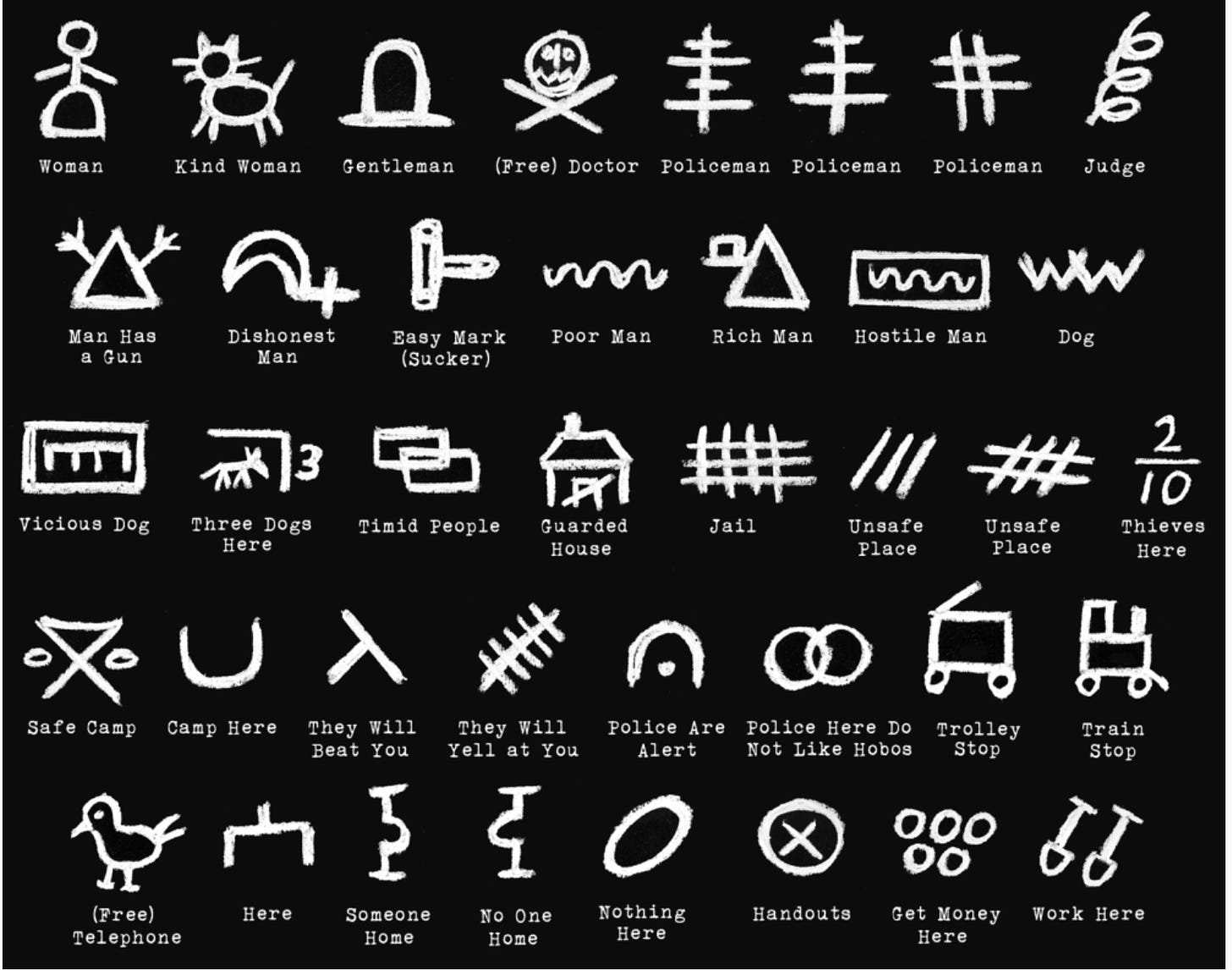

If he didn’t keep his word, and thus sullied his name, he might have to change it. When Dick Whitman—whose father’s house was branded with a hobo mark meaning “a dishonest man lives here”—showed cowardice in Korea, he changed his name to Don Draper, and set about building the alliterative words into a brand using the tools of advertising.

Trump’s father, too, was a dishonest man who perjured his name. The family name had once been Drumpf. So Trump was never a good name, either to sully or uphold. For the real Donald, as with Don Draper, there was, then, only a chance to build an anti-name—a name that means something like he leaves no word unkept. As names, words, brands, and laws are all tangled up etymologically (see: logos and nomen in Latin, nomos in Greek), an anti-name brings to mind Martin Luther’s idea of antinomianism, or the rejection of laws and legalism—and moral, religious, and social norms.

A man who doesn’t keep his word, in other words, defies moral codes and loses his good name, winning instead the “dishonest man” logo, the anti-name, and his dishonesty ends up being a brand in itself.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Magic + Loss to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.