I’ve almost given up trying to dial down widespread panic about kids and digital media.

Maybe the cortisol induced by nightmares that our children are screen-poisoned is keeping our very hearts beating.

Sure, in my view, we put way too much blame for phantom psychological problems, formerly known as sins, on screens. With physical problems, we likewise blame food. Intuitive eating and intuitive screen use— involving so little overthinking that you don’t really think about food or screens at all and instead think about truth and beauty—is my approach.

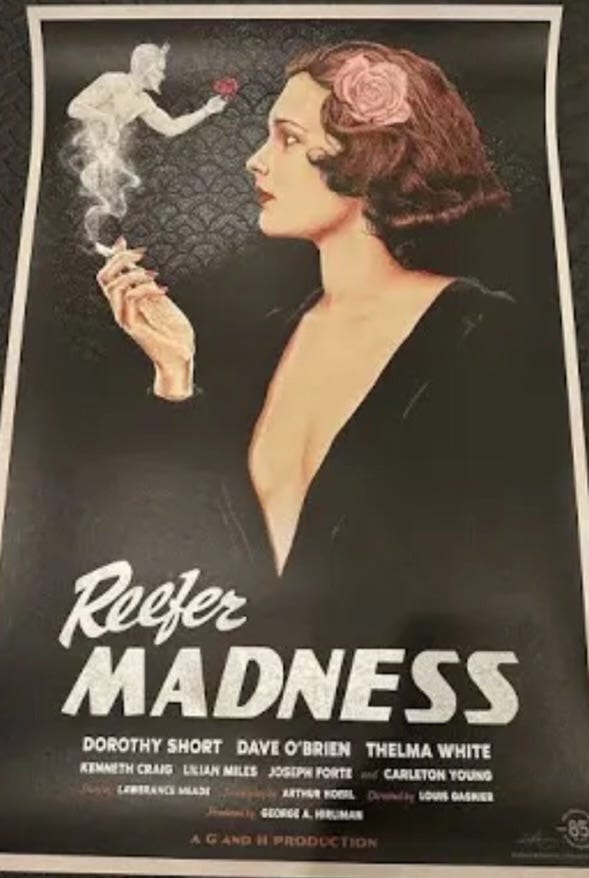

But it’s no surprise that Jonathan Haidt, in his latest book about “the great rewiring of childhood,” maintains—against a backdrop of almost zero popular dissent—that screens are making kids flat-out insane. The book freaks out about the fate of modern youth in a way not seen since the great mental-hygiene films of the ’50s. The argument of The Anxious Generation has the advantage for Haidt of making adults flat-out insane and then offering itself as the solution. Naturally it’s #1 on the book leaderboard.

(Haidt I’m sure would advise against buying the e-book, or using the Audible app to listen to it, or watching Haidt’s hundreds of promos for it on YouTube, TikTok, and Instagram.)

My first question is about Haidt’s title, and that “great rewiring of childhood.” This is science, so let’s get to the facts. Where are the electrical cables of the phase of life called childhood, such that these cables can be spontaneously pulled out and reinstalled? I don’t know social science but I always admire the pop-science trick of forcing a puff of fanciful poetry—”the rewiring of childhood”—to conjure an occult process that points to nothing real in science or history, and then predicating a vast, hyperbolic argument on it.

Fortunately, the would-be science in The Anxious Generation has been ably dismantled by Nature, an actual science magazine. “Rising hysteria could distract us from tackling the real causes [of mood disorders],” writes Candice L. Odgers, UC Irvine dean for research and professor of psychological science and informatics, in Nature. “The book’s repeated suggestion that digital technologies are rewiring our children’s brains and causing an epidemic of mental illness is not supported by science.”

Even if Haidt the apocalyptician weren’t a father and Odgers the skeptic weren’t a mother I’d still describe this broader debate as gendered. Anthropology has cautioned again and again against imagining that history proceeds as a series of male-authored “revolutions”—from agricultural to scientific to industrial to digital—that “change everything,” and then are recapped by other alpha males as catastrophic.

Archaeological evidence, as laid out especially by David Wengrow and David Graeber, suggests much more improv, much more patchwork. What’s more, in The Dawn of Everything, they propose, with evidence, that much scientific method, and thus science itself, seems to have emerged in the trial and error of cooks, housekeepers, mothers, and nurses—mostly women—and not in models of pocket-sized telephones or factory production proposed by men whose names we know.

Social media for most parents, in the particular, with their particular children, is just not all that harrowing. While 58 percent of adults are worried about social media, only a quarter of actual parents describe themselves as “extremely concerned” the way Haidt is. At my house, it’s very hard to see a kid laughing at a group chat or an SNL video and become extremely anything except passingly curious about the timing of Michael Che.

My other kid, who’s in college and also a teenager, has never owned a phone—and while I’m sure Jonathan Haidt would find that heartwarming, I can attest that an adolescence spent without a smartphone has led to or exacerbated plenty of real-world dangers, including a health emergency in Delhi and a weather emergency in Reno. I don’t need to summon up obscure modern hazards (flashes of ADHD) as symptoms of phone use; the very real dangers of non-phone use are those that land you in the emergency room or the Reno airport at 4 a.m. sleeping under the slot machines.

(To those mothers of stubbornly phone-free kids who have had to call Uber to remote locations that can only be guessed at, who field urgent texts from a kid’s friends when he’s unfindable, and who print out maps and plane tickets only to release a kid with them into the vast payphone-less world—in which your kid must borrow the phones of strangers when he’s in trouble—I’m here for you. I imagine you’d agree that a little Instagram or Duolingo every now and then would be a small price to pay if it meant your kid had access to Google Maps and 911.)

But I’m not concerned about my son’s choice; it’s his. Likewise, my daughter’s choice to have a phone is hers. And your kids? I promise never to opine on what they do and don’t do with screens. So I put myself squarely with the 48 percent of parents (nearly half!) who describe themselves as simply not very concerned about social media—either “somewhat concerned” or “not concerned at all.”

When staticky black-and-white TV sets first made their way into lucky American living rooms in the late 1940s, children’s shows like the Western-circus mashup “Howdy Doody” weren’t reviled by parents. Instead, they seemed like a miracle.

Much of the most anxious work of mid-century American mothers was preventing and treating injuries, fights, accidents, attacks, and outbursts. City kids fell out of windows or got beaten up; country kids drowned or got beaten up. Emotional outbursts, then as now, could make kids targets of aggression by their fathers and clergy and teachers, so the maternal work of quieting kids doubled as a health measure. In those days, after all, some 51 out of 1,000 infants died before their fifth birthday. Nearly twice as many people per capita died in accidents then as now.

Even if it weren’t such an innovative and charming show, “Howdy Doody,” in preventing violence and accidents and tantrums, was downright astonishing. Not only did it engross and amuse kids for a full hour, feeding their imaginations; it also kept them quiet, orderly, and safe. Somehow, when the TV was on, the kids didn’t wreck rooms or draw blood from their siblings or torture the pets. Now that is a good show.

And for even the most rigid mother, it was also hard to find fault with Howdy, a patriotic ginger puppet who had 48 freckles, one for each state of the union, until 1959, when he got his Alaska freckle. Because money was tight and actors with talking parts had to be paid scale, Clarabell, the delightfully mute clown, communicated in mime.

Why would a stay-at-home mother find fault with “Howdy Doody” anyway? They got a break from worry, from splinting broken bones, and, best yet, from having to put on a show themselves. This was an especially welcome development in the hinterlands, where there was very little formal children’s entertainment: no theater, no cinema, no circuses.

My grandfather, Lyle Coffey, anticipated this. I acquired at least some of my confidence in media to measurably improve lives, and certainly my skepticism that it’s some kind of neurotoxin, as he told stories of introducing cable television in the coalfields of McDowell County, West Virginia, in the early ’50s. This was before the pleasures of Howdy and “Captain Kangaroo” had even come to New York City. When you grow up in the country, it’s exhilarating to be first—and connections to the outside world, from newspapers to WiFi, are more precious than they are in cities, which are “the outside world.”

In a dangerous and troubled mining town short on attractions, it was a boon to have a way to entertain kids with almost zero risk. Cable in those days cost families $4 a month, and everyone in town signed up and kept paying. My aunt Jane, who had Down Syndrome, was especially delighted by “Howdy Doody,” as was my grandmother, who got from the show a short, much-deserved break from caregiving.

But the delight of female caregivers in TV seems to have bothered moralists.

Yes, no sooner had “Howdy Doody” and “Captain Kangaroo” filled houses with songs, happy voices, applause, and infectious laughter, parental panic kicked in. Not long ago, the so-called Scarsdale Moms—Scarsdale had just been born as a ludicrously rich suburb of New York City—had complained that radio programs were “overstimulating, frightening and emotionally overwhelming” for kids. They compelled the National Association of Broadcasters to vow never to glorify greed or disrespect for authority.

When TV became the focus of scolds, the president of BU took the time in 1950 to tell graduating seniors, absent evidence, that television was ruining them. “If the television craze continues with the present level of programs, we are destined to have a nation of morons.”

(“The present level of programs,” of course, was a handful of network shows a day and nothing at night.)

Haidt, a business psychology professor, claims in his book that he wants to bring back “play” to childhood. Leaving aside the question that play and screens are hardly incompatible—does he define play as to exclude Minecraft and Wordle?—he throws in with the Scarsdale Moms in rejecting screen time as overstimulating, frightening and emotionally overwhelming.

But Haidt goes a step further, saying “the phone-based world in which children and adolescents grow up is profoundly hostile to human development.”

Is it? Profoundly? And hostile to human development—that sounds terrifying unless we ask what it might mean. What’s human development, exactly? Is it defined to be “that which cannot happen if you have a smartphone”? Is it defined as “that which happened to the highest degree in the 1950s or 1980s or 1800s but abruptly stopped happening 12 years ago”?

And can a “world” be hostile to this development, the way a desert might be hostile to certain vegetation? And what is a “phone-based” world? One in which people have phones? Have smartphones? Use smartphones every second of every day? And can the world ever be said to be grounded, somehow, in a single technology?

I ask but don’t answer these questions in part because Haidt himself says he’s against moral absolutes, and claims the most important thing to ask yourself in a debate is “what game am I playing and what game is my partner playing?” I suspect Haidt is playing the language game called “a nonfiction bestseller” which consists of meme-making with mixed metaphors to spike delectable doses of fear. This is a lucrative game, but I’m too tired to counter.

However, it is worth pointing out that if you’re worrying about sinister turns of events online, you may not be looking at what people are actually doing on their phones. YouTube is still the most popular app for kids, and the most popular videos on all of YouTube—for kids and adults alike—are Baby Shark Dance (14.52 billion views!), Despacito, Johny Johny Yes Papa, Bath Song, The Wheels on the Bus, Phonics Song with Two Words, Learning Colors, and Baabaa Black Sheep. For teens looking at the top vids, there’s Shape of You and Uptown Funk.

All of these are music videos—and most are even what we used to call educational. Several of them are for adults and kids learning English as a second language. No revenge porn or cyberbullying or thinspiration anywhere. Can kids find that stuff deeper on the site? Sure. But why not give an analysis of the stuff real kids are actually watching, in views by the billions, instead of what makes tragic news or surfaces as shocking on Twitter in Scarsdale?

Katie Foss, a media studies professor at Middle Tennessee State University, says that with social media, “all we are doing is reinventing the same concern we were having back in the ’50s.”

And the panic may go back even further. In the 1920s, Sidonie Matsner Gruenberg, a proponent of play and above all toys, rejected what she saw as "arbitrary puritanism” in American parenting. American parents, she argued, suspect "every desire and impulse of being Satanic.”

You know what I think is Satanic? Or a bad game, anyway? How Haidt and other pundits want us to hate ourselves for using phones for social contact and cultivate suspicion of our kids for doing exactly what we do. Sure, don’t buy your kids expensive phones and lobby their schools to forbid them in classrooms, if you want; that sounds thrifty and sensible.

But believing that Snapchat is the devil’s work? Wrenching away a kid’s phone so he can’t talk to his friends? Assuming that kids are so feeble that they can’t look at photographs and portraits without turning to self-harm? That sounds not conscientious but barbaric.

I'd love to have been able to ban smartphones from my college classroom, but doing that on my own hook would have sent my evaluations crashing through the floor. My sense is that the danger of social media is that they plunge the user into the halls of a gigantic hellish middle school in which they're subject not only to the bullying of their classmates but of kids from other schools across the English-speaking world and, worse, of sadistic and exploitative adults. This isn't a problem inherent in screens; it's a problem inherent in a boundary-less social sphere.

On a side note, Clarabell was played by Bob Keeshan, who later moved up from a silent character part to the lead on Captain Kangaroo.

Has anyone linked this panic to the research finding that mindfulness training makes teens more depressed, mainly by getting them to think more about the world. I'm nearly 70, born with an optimistic temperament, and thinking about the world (Trump, Putin, Gaza, global heating) makes me really depressed.