Jury trials focus on human bodies. Intently, almost pruriently.

In common law, habeas corpus—“you shall have the body!”—means a person who’s charged with a crime must appear, physically, before a judge.

This is not just for the judge but for the defendant. A writ of habeas corpus is an order that an authorized official bring a defendant before the court so a judge can be sure the body is safe and the detainment is lawful.

Likewise, a jury of the defendant’s peers—often in part selected for features of their bodies, including skin color and secondary sex characteristics—must appear in person. We assume that, only in sharing a room with the defendant’s body, can jurors see what they make of him.

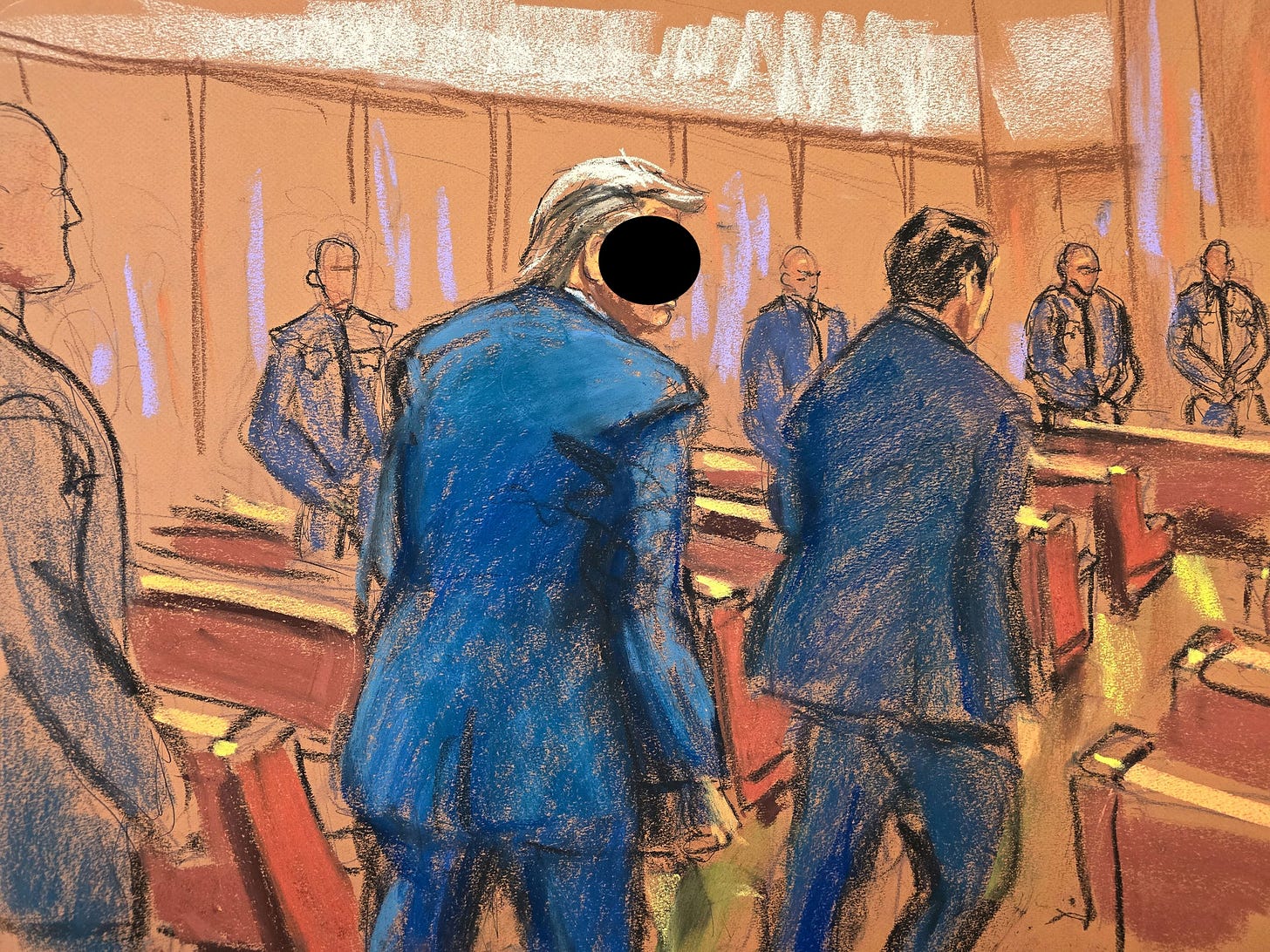

“Sometimes lumbering,” “gesturing and shaking his head,” “craned his neck to the right,” “reserved, quiet,” “always stone-faced,” “appears to briefly nod off,” “his mouth kept going slack,” “his head drooping onto his chest,” “alternately irritated and exhausted,” and of course the unconfirmed rumors of Trumpian courtroom flatulence. These observations of Donald Trump, during his criminal trial in Manhattan, come from CBS News, The New York Times, and Mediaite.

But it’s not just Trump’s body that’s open for discussion this week. Before the trial even began on Monday, Judge Merchan repeatedly mentioned human aches, needs, frailties, and vulnerabilities.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Magic + Loss to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.